"Kenny” was in his early 20s when I first met him. He was from one of the hill towns of Rensselaer County and was recently married. Kenny had been arrested in Troy for the robbery of an 82-year-old man on Troy’s south side. He claimed indigency, and I was assigned to represent him in Troy Police Court. A preliminary hearing was conducted, and the evidence against him was credible. The elderly victim was unwavering in his identification of Kenny as the attacker, as was an eyewitness to the event. The victim belonged to a senior citizens center, and he had a lot of support and sympathy. The police court judge, Timothy Fogarty, was running for election to become the Rensselaer County Judge, and it was politic for him to be stern. He held Kenny over for the grand jury. To be fair, the prosecutor easily met the burden necessary for the case to be heard by the grand jury, which promptly indicted Kenny on a charge of first-degree robbery, but Kenny was released on bail.

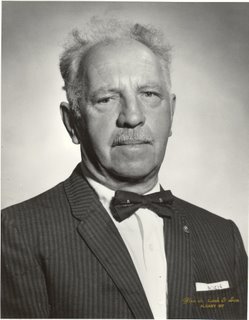

Kenny’s case was reached for trial the following spring. By then Tim Fogarty had become County Judge Fogarty. The trial did not go well for Kenny. I asked Judge Fogarty to disqualify himself because he had previously heard the evidence when he conducted the preliminary hearing, but he refused. The District Attorney was unwilling to accept a plea bargain that would have permitted Kenny to serve a year in the county jail, and Kenny was unwilling to agree to any longer sentence. A jury was picked, and the trial was conducted before an audience of senior citizens. Judge Fogarty, always pompous, played to the crowd and gave every break to the prosecution, and none to the defense. The trial lasted just one day. The victim again told his story of the robbery, and the police told how they determined that Kenny committed the crime. Kenny did not testify and had no witnesses on his behalf. At one point the jury asked to have testimony read back to them, but Judge Fogarty refused. The jury quickly convicted Kenny of robbery in the third degree.

Although the judge’s law clerk advised him that he had made a reversible error by not having the testimony read back to the jury, and he should declare a mistrial, Judge Fogarty was not about to admit his mistake, and he let the verdict stand. Kenny was sentenced to a term in state prison and was sent off to Clinton Prison in Dannemora, Clinton County.

I appealed his conviction to the 5 judge Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court. Even the district attorney considered a reversal of the conviction to be a certainty because of Judge Fogarty’s error. To everyone’s surprise, the conviction was affirmed. The appellate court unanimously decided that the evidence against him was so overwhelming that the conviction should stand. Everyone was shocked. I had done my best and considered the legal proceedings concluded.

Kenny’s wife had a young child and she became a welfare recipient. She desperately wanted Kenny home, but I told her that there was nothing more that I could do. Her minister came to see me, and I also explained to him that Kenny would have to serve out his term, less any time off for good behavior, and perhaps early parole. In any event, he would probably be in prison for at least three more years.

During my frequent trips to the Court House, I repeatedly noticed that Kenny’s wife and her minister sitting in the anteroom of Judge Fogarty’s chambers. Kenny’s wife always brought her infant with her, whose crying or babbling clearly irritated the judge’s secretary. I learned that they would come to see Judge Fogarty two or three times each week, sitting and waiting until he would see them. Although he explained that there was nothing he could do and dismissed them, they persisted. Finally, he called the New York State Corrections Department and said that he wanted to reduce Kenny’s sentence. He was told that it was too late; the sentence was final and he had no authority to modify it. Although he had tried to help Kenny’s wife get her husband home early, he became irritated by her continuing visits, always accompanied by her minister and young child.

I told Judge Fogarty that I knew of no grounds for bringing a Coram Nobis proceeding for Kenny. He told me to raise any possible issue that sounded plausible and make it returnable at the next County Court motion term because he was going to grant the petition. He sent a court order to the warden of the Clinton Prison directing that Kenny be released to the Rensselaer County Sheriff to bring him to Troy for a hearing. He told the Sheriff to be sure to bring all of Kenny’s possessions with him.

I drafted a minimal petition. The district attorney didn’t contest the petition, and the victim had since died. Kenny’s conviction was vacated without fanfare, and he was released to the joyful arms of his wife. I never heard from him, or about him, again.

Although Judge Fogarty enjoyed his large, well-appointed chambers in the Rensselaer County Courthouse, which were much grander than the small room in the Troy Police Court located on the second floor of the police station, he was plagued by the view from the easterly window which looked out across Congress Street to a new Jack in the Box restaurant at the corner of Congress and Third Streets. This fast-food restaurant had its trademark Jack in the Box clown head atop a tall pole which brought it almost to the same height as Judge Fogarty’s window. When the restaurant was open for business, the clown head would rotate, and Judge Fogarty would see this smiling clown out of the corner of his eye. He would frequently send a court officer to the restaurant to direct the manager to turn off the rotation and stop it with the clown's facing away from his window.

Although Judge Fogarty enjoyed his large, well-appointed chambers in the Rensselaer County Courthouse, which were much grander than the small room in the Troy Police Court located on the second floor of the police station, he was plagued by the view from the easterly window which looked out across Congress Street to a new Jack in the Box restaurant at the corner of Congress and Third Streets. This fast-food restaurant had its trademark Jack in the Box clown head atop a tall pole which brought it almost to the same height as Judge Fogarty’s window. When the restaurant was open for business, the clown head would rotate, and Judge Fogarty would see this smiling clown out of the corner of his eye. He would frequently send a court officer to the restaurant to direct the manager to turn off the rotation and stop it with the clown's facing away from his window.