It was an easy and enjoyable transition from a criminal defense attorney to a prosecutor. There were great resources available to the prosecutors. The police agency that arrested a criminal defendant was obligated to do any follow-up investigation, and the office also enjoyed the services of Jack Dwyer and Joe Burns, two experienced police officers who were employed full-time as investigators. Additionally, the prosecutor could choose to not prosecute a weak case, or to plea bargain down a questionable case.

It was an easy and enjoyable transition from a criminal defense attorney to a prosecutor. There were great resources available to the prosecutors. The police agency that arrested a criminal defendant was obligated to do any follow-up investigation, and the office also enjoyed the services of Jack Dwyer and Joe Burns, two experienced police officers who were employed full-time as investigators. Additionally, the prosecutor could choose to not prosecute a weak case, or to plea bargain down a questionable case. The assistants would rotate handling cases. We were all part-time employees with private law practices. Troy Police Court, which provided the bulk of cases handled by the office, took up the mornings for one or two weeks each month, depending upon the rotation. The same assistant would usually handle subsequent felony hearings for defendants arrested during his rotation and present the case to a grand jury. We would also handle town court cases one or two evenings a week.

I was very familiar with the workings of the district attorney’s office. I took a summer job in that office between my second and third years of law school. The summer jobs in county agencies were usually given to the high school or undergraduate college students who were children of political committeemen of the party that controlled the agency. I was able to get the job because my uncle, Harry Honig, was the Nassau Town Supervisor. I had just completed a criminal law elective taught by John T. Casey, then the District Attorney and an adjunct professor at Albany Law School. I was not expected to do much more than observe, as summer help wasn’t expected to do much work. However, I usually went to Troy Police Court each morning with one of the three assistants, Jim Reilly, Pierce “Bud” Russell, or John Burke, and they utilized me to do research and draft court documents, thus freeing more of their time for their private practice. I was given access to all of the open and closed files. I sometimes found closed cases involving people I knew, including a criminal prosecution involving the sexual activity of a couple of high school classmates. There were no trials to watch because the Supreme Court and the County Court did not hold trial terms during the summer months. I was a good typist (out of necessity because I have terrible handwriting), and Kay James, Mr. Casey’s confidential secretary, frequently asked me to write letters reducing motor vehicle charges in town courts “in the interest of justice.”

A couple of months after I became an assistant district attorney, a bookstore opened on Broadway in Troy. Soon, complaints rolled into the police that the store was selling pornography. This was in the days of Ozzie and Harriet reruns, and the citizenry was outraged that such materials should be sold at all, particularly across from the Post Office and within a couple of blocks of two churches. Gus asked me to look into the situation, so one morning I enlisted Jack and Joe and we went to the book store and looked at the merchandise. Although some of the magazines were of the Playboy genre, there were a lot of magazines and 8 mm movies with suggestive covers that probably would have shocked Ozzie and caused Harriet to faint. I decided that there was sufficient evidence for a prosecution. Jack and Joe locked the door and announced that they were police officers and were arresting the sales clerk for the sale of pornography. At the time, there were a couple of patrons in the store who panicked at finding themselves locked into the store where an arrest for pornography was taking place. Jack and Joe took their names and let them out of the store. We filled several boxes with the most pornographic magazines that we could find, as well as the movies that had the most suggestive titles, and brought them back to the office. The clerk, a young man who was merely an employee, was charged in Troy Police Court with the sale of pornography.

We learned that the store was actually leased by a Massachusetts corporation, and I received a telephone call from its attorney, who told me that the corporation had several such stores in New England, and the Troy store was its first in New York. He told me that “accommodations” could be made if the prosecution was dropped, a suggestion I didn’t care for as it hinted at a bribe. I told him he had a serious problem because the Massachusetts corporation hadn’t filed the necessary papers with the New York Secretary of State to conduct business in New York, which he said must have been overlooked, which he promised to correct.

When the clerk’s case came on for a hearing in Troy Police Court, he was represented by a prominent local attorney hired by the corporation. The attorney gave an impassioned statement that it was wrong to criminally prosecute this young man, who was merely trying to earn a living selling what he had been told was perfectly legal merchandise. I told the court I agreed and went on the record dismissing the charge and granting him immunity from prosecution. The attorney’s pride at having convinced me to drop the charges against his client faded away when Jack immediately handed the clerk a subpoena to appear before the grand jury the next day. Having immunity, the clerk had to testify, and the grand jury handed up a sealed indictment charging the Massachusetts corporation with the pornography crime. By then, the corporation had filed its certificate to do business in New York, a condition of which required the corporation to agree to the jurisdiction of New York courts for acts committed in the state and appoint the Secretary of State as the corporation’s agent to receive and forward legal process. The indictment was thus served on the corporation.

The Massachusetts corporation did not roll over. It immediately commenced a lawsuit against Gus, me, and the County of Rensselaer in the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York to enjoin the criminal prosecution as a violation of free speech and for damages. The first appearance came in the federal court in Albany before Judge Foley, a resident of Troy. The corporation’s attorney made a very eloquent presentation, but Judge Foley protested that he didn’t know what was or was not pornography and refused to look at the several examples I tried to hand up for his inspection.

A compromise was reached after some conferences with the corporation’s local attorney. The corporation withdrew its lawsuit and closed the bookstore with an understanding that it would not return to Rensselaer County. The corporation pleaded guilty to a reduced charge and paid a fine.

One morning, I returned to the District Attorney’s office just before noon to drop off the morning's Troy Police Court files. It had been a busy session. I was eager to return to my private office to check my calls and go for lunch with Jim. When I walked in, Tess, Gus’s confidential secretary, told me that Gus wanted me to cover for him at a convocation of mental health professionals at the Veteran’s Administration Hospital in Albany. Gus was scheduled to be a speaker at the one o’clock session to give a prosecutor’s viewpoint on suicide prevention and other legal mental health issues. Unfortunately, Gus was tied up in a trial in County Court and couldn’t break free to fulfill the commitment.

As I drove to Albany, I thought about what I could say about the legal aspects of suicide prevention to a group of psychiatrists and psychologists. Mentally, I pieced together a brief talk that centered around one method once used in the United Kingdom to discourage suicide: all property owned by the person committing suicide would be seized by the Crown, the thought being that no one would want to financially punish his family by impoverishing them by his suicide.

I arrived at the VA Hospital and was ushered into the auditorium and onto the stage just as the group returned from lunch for the afternoon session. Gus was one of three scheduled speakers, the others being a minister and a New York State Police senior officer. The minister was up first, but he announced he wanted to give his time to two other men he had brought along. He introduced two young men who held hands and spoke about how they and other gay men frequently thought about suicide because they were continually harassed, particularly when being together in Washington Park. I sat there thinking, “I am missing lunch for this crap?”

The officer was up next, and to my dismay, he gave practically the same talk that I had been planning. (I later learned that he had attended but not graduated from Albany Law School and learned the same history of suicide from Dean Clements, who taught criminal law to first-year students.)

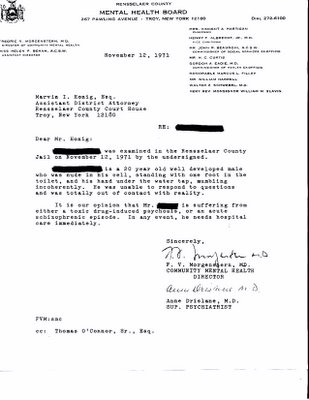

Suddenly, it was my turn, and I had no idea what to talk about when I was introduced. I decided to talk about a young man whose prosecution I had been handling in Troy Police Court. He was on suicide watch at the Rensselaer County Jail. He was originally arrested for setting fire to some street trash. A psychiatric examination was requested by his assigned counsel, Thomas O’Connor, Sr., and Judge Fogarty reported that Dr. Morgenstern, the director of the county’s Mental Health Board, had found him to be “sound as a dollar.” He was released on bail but was soon rearrested while walking nude up the center of Hutton Street, telling the arresting police that God had instructed him to show people what a real man looked like. After this arrest, a formal two-physician examination was ordered. The result was as follows:

I then spoke about how the legal profession viewed (at least in my view) psychiatrists. I said that lawyers had little regard for psychiatrists as witnesses as they would usually find whatever results were needed by the employing attorneys. As an example, I mentioned the case of a fourteen-year-old boy charged with juvenile delinquency who I represented as his law guardian in Family Court a couple of years ago. The boy admitted to shooting his father in the head with the father’s handgun, and the issue was what the disposition should be. The County Attorney (who prosecutes juveniles in Family Court) produced a psychiatrist who testified that the boy was dangerous and should be confined. I produced a psychiatrist who testified that the only person ever in danger by the boy was his father, and since his father was dead, there was no medical reason to confine him. [The boy was placed in the custody of his paternal grandmother.] I mentioned that our County’s Mental Health Director was routinely referred to as “Dr. Foreskin” by Judge Fogarty and many defense counsel and prosecutors who routinely practiced in Troy Police Court. That statement brought murmurs from the audience.

Later that afternoon, Tess telephoned and asked me to come to the District Attorney’s office. When I got there, she told me that Gus was getting repeated calls from Dr. Morgenstern, who had received reports about what I had said from some of his staff members who had attended the convocation. Gus was still in court, and Tess was worried about what to tell him. When Gus came in and I told him what happened, he laughed and said he would “calm Foreskin down.”

A short time later, I was drafted by the incoming Republican-dominated County Legislature to be County Attorney. As such, I became the attorney for all county officers, including Gus and Dr. Morgenstern. Gus went on to become Rensselaer County Judge, New York Supreme Court Justice, and United States District Court Judge. Dr. Morgenstern retired to Palm Springs in the 1980s.