This is my place to share some memories I have of growing up in the rural town of Nassau, Rensselaer County, New York, and later practicing law in upstate New York. Recent Posts on the sidebar show only the most recent posts, but all are visible as you scroll down the main page. The posting dates are merely to put the posts in a sequence. The posts start with my youth, then to adulthood and practicing law, as well as items relating to Nassau. Some images will enlarge if clicked.

Friday, January 01, 2021

Captive Love

Tuesday, December 01, 2020

Kenny Gets Out Early

Although Judge Fogarty enjoyed his large, well-appointed chambers in the Rensselaer County Courthouse, which were much grander than the small room in the Troy Police Court located on the second floor of the police station, he was plagued by the view from the easterly window which looked out across Congress Street to a new Jack in the Box restaurant at the corner of Congress and Third Streets. This fast-food restaurant had its trademark Jack in the Box clown head atop a tall pole which brought it almost to the same height as Judge Fogarty's window. When the restaurant was open for business, the clown head would rotate, and Judge Fogarty would see this smiling clown out of the corner of his eye. He would frequently send a court officer to the restaurant to direct the manager to turn off the rotation and stop it with the clown's facing away from his window.

Although Judge Fogarty enjoyed his large, well-appointed chambers in the Rensselaer County Courthouse, which were much grander than the small room in the Troy Police Court located on the second floor of the police station, he was plagued by the view from the easterly window which looked out across Congress Street to a new Jack in the Box restaurant at the corner of Congress and Third Streets. This fast-food restaurant had its trademark Jack in the Box clown head atop a tall pole which brought it almost to the same height as Judge Fogarty's window. When the restaurant was open for business, the clown head would rotate, and Judge Fogarty would see this smiling clown out of the corner of his eye. He would frequently send a court officer to the restaurant to direct the manager to turn off the rotation and stop it with the clown's facing away from his window.Sunday, November 01, 2020

Cruel and Inhuman Treatment

Thursday, October 01, 2020

Judge Filley Retires

Judge Filley Retires

Marcus L. Filley was the scion of an old Rensselaer County family. His grandfather, for whom he was named, owned a stove-making foundry in Troy during the mid-19th century. (An interesting article about his grandfather is available at http://www.lib.rpi.edu/Archives/access/inventories/manuscripts/MC12.html)

“Mark,” as he was known, was born in 1912 and graduated from Williams College in 1933. After playing one undistinguished major league baseball season for Washington in 1934, Mark followed in his father’s (and grandfather’s) footsteps and went to law school. He set up practice in Troy and was elected the first Children’s Court Judge in Rensselaer County. He became the first Family Court Judge in the early 1960s, when the court was established. Mark was tall, slender, and a distinguished-looking man who wore tortoiseshell glasses. He was considered a real gentleman.

As a Family Court Judge, he was fair, albeit somewhat indecisive. In fairness, most Family Court cases involving support and/or child custody are without a clear-cut resolution. In most cases, no one is happy with the Court’s decision. The father is unhappy because he feels that he is paying too much support and not getting enough visitation; the mother is unhappy because she is going to receive too little support, and the only reason that the father is seeking more visitation is to annoy her, since he really had no interest in the children when they were living together. The attorneys are unhappy because they didn’t achieve the result their clients wanted, and the judge is unhappy because he knows that he has not pleased anyone and will likely have the parties before him again, arguing about the same problems or alleging that the other spouse has violated the court’s last order. Judge Filley usually tried to mediate rather than arbitrate. It was common in support and custody cases for him to say, at some point in the proceedings, “Gee whiz, folks, can’t you folks agree on...”. Many attorneys who frequently practiced in Family Court referred to him as “Gee Whiz” when speaking with each other.

Aaron was, by all accounts, a brilliant young mathematics professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (“RPI). Although he was only in his late 20s or early 30s, he held a PhD in mathematics from a top university and had studied and taught in Europe before taking his position at RPI. While in Europe, Aaron met and married Eva, a comely young lady from Budapest. Aaron and Eva moved to Troy, where Eva gave birth to a son.

Eva did not adapt well to living in Troy. She spoke little English and was uncomfortable with its culture. She felt uncomfortable socializing with other faculty wives and preferred staying home with her child, while Aaron thrived in this environment. Eventually, Aaron left, and they divorced. In the absence of a support and custody agreement, the Court granting the divorce referred the matters of alimony, child support, and visitation to the Family Court.

By the time their case came up in Family Court, Eva had, of necessity, taken a part-time job as a waitress in a neighborhood restaurant in Watervliet. Somehow, Judge Filley made an order of support requiring Aaron to pay $37.50 per week for child support, but nothing for alimony, since Eva was employed. However, in fact, her earnings, after paying for babysitting, were a poverty wage. Aaron was also ordered to continue paying rent and utilities on the small apartment in which Eva and their son were living.

Adding to Eva’s financial woes was her distrust of American physicians, which was likely partly due to her limited ability to communicate with them. Whenever she or her son was ill, she would call her family physician in Budapest for advice. If either of them had to see a physician in Troy, Eva would call her Budapest physician to discuss the treatment or medicines that had been prescribed. She also called her mother frequently to discuss her plight. Her telephone bills were extraordinary, and she was distraught.

On someone’s advice, Eva started writing letters of complaint. First, she wrote to Judge Filley, who wrote back that he could not discuss her case with her. Then, she started writing to appellate judges complaining about Judge Filley. Finally, she was advised to get a new attorney and request a rehearing. At that time, she hired Jim Smith, a Troy attorney whose practice primarily focused on matrimonial and family law. I was engaged to represent Aaron, whose former attorney declined to represent him on the rehearing.

It was a terrible morning in Family Court. Eva wept and complained about her poverty, her son’s illnesses, about living in a strange land without friends, and Aaron’s broken promises. Child support of at least $100.00 per week would help alleviate her misery. Aaron blamed Eva for her problems. She should have made a greater effort to learn the language of her new homeland and to make friends. It was an absurd waste of money to call a physician in Budapest when there were fine doctors in Troy whose medical fees were substantially covered by his RPI health insurance program. She could work longer hours at the restaurant and add to her income. Furthermore, the Court had already determined $37.50 per week, and there had been no change in the circumstances. Judge Filley’s “Gee, whiz, folks...” plea fell on deaf ears. He called a recess and called Jim and me into his chambers.

Mark told us that he thought both of our clients were crazy, and he wanted us to work out a compromise agreement. He adjourned the matter until after lunch to give us time to consider. Jim and I tried our best to come to a resolution. I suggested $60.00 per week, and Jim suggested $75.00 per week. Aaron refused to come up from $37.50, and Eva didn’t want to consider anything under $100.00.

Judge Filley ascended to the bench promptly at 1:00 pm. He called Jim and me to the bench and inquired whether we had reached a resolution. We told him there had been no movement in our clients’ positions, although we felt there was some middle ground. Judge Filley told us that he would leave the bench forever rather than decide the case. He announced on the record that he was feeling ill and was going to visit his physician. He adjourned the hearing and walked out of the courtroom. He never returned to the bench. He took some medical leave, and upon its expiration, he resigned his judgeship and opened a law office on First Street in Troy, where he did not practice matrimonial or family law.

With Judge Filley on medical leave, the judicial administration assigned Family Court judges from other counties to cover Judge Filley’s calendar until his successor was appointed or elected. Montgomery County Family Court Judge Robert Sise was assigned to hear and decide Aaron and Eva’s case. Following a brief hearing, Judge Sise ordered Aaron to increase the weekly payments to $95.00 per week. Eva was elated, although not entirely satisfied. Aaron was shattered! He thought the decision was punitive and wanted to immediately appeal. I advised him that the decision would not be overturned on appeal. He said he would not pay, and I told him that if he didn’t pay, he was subject to being held in contempt of Court. In any event, his salary at RPI would be subject to a garnishee order from the Court as soon as he missed a payment, and the support would simply be deducted from his paycheck.

I never saw or heard from Aaron after that. Jim Smith reported to me that Aaron simply packed up his belongings and moved to Europe, where he secured a teaching position at a college far beyond the reach of the Family Court. Eva was trying to save money to pay for transportation for her and her son back to Budapest.

Tuesday, September 01, 2020

Habeas Corpus

Jimmy was an alcoholic. He was what you would call a “stinking drunk”. He looked frail and bent over, even on his best days. In the early 1960s, public intoxication was still a criminal offense, and when the Troy police found Jimmy lying drunk on the street, they would cart him off to jail on a charge of public intoxication, a misdemeanor.

Jimmy was never brought to trial on the charge. Instead, he would just be kept in jail for however long it took for him to sober up and feel ready to reenter society. Jimmy would then ask his jailers for paper and pen and carefully handwrite a petition for a writ of habeas corpus addressed to the Rensselaer County Supreme Court. There was an understanding that when Jimmy wrote his petition, he was sober and ready to be released. No hearing was necessary, and a telephone call from the Court clerk to the jail put Jimmy back on the street without fanfare.

Saturday, August 01, 2020

Robert Kemp

Bob Kemp came from an old, illustrious Troy family. An ancestor had founded the Burden Iron Works in the 1800s when Troy was in its industrial heyday. It was the major supplier of horseshoes to the Union Army during the war between the states and a supplier of rails when the west was opened.

Robert’s troubles reportedly started during the early 1930s. Although he was unpopular as an atheist in a very Catholic city, he became hated as an avowed communist, going so far as to publish small books (one of which he showed me) in which he listed himself as “Robert Kemp, Chief Engineer to Josef Stalin, Troy, CCCP.” (Copies are available at the Troy Public Library and the Library of Congress*) He was openly jeered, and his home at 552 Fourth Avenue in the old Lansingburg section of Troy was frequently damaged by young vandals. He was known in Lansingburgh as “Commie Kemp.” He said that sometime after WWII, he became an anti-communist. In a legal pleading, he described himself as “an inventor, scientist, pioneering engineer, venture capitalist, an anti-communistic businessman, an Atheist, and a Heretic.”

At some time before 1963, vandals set fire to his home, causing considerable damage, which he could not repair. Eventually, the City of Troy commenced an action against him and obtained an order directing the demolition of his house as unsafe and a danger to the community. A default judgment was taken, and a judge signed the order permitting the building’s demolition. Shortly before the demolition was to occur, Kemp went to Judge Donald Taylor and pleaded for help. The judge issued a stay to permit Kemp to appeal the order to the five-judge Appellate Division. Kemp threw himself into the appeal (which was the stage of the matter when I met him).

Kemp based his appeal on the theory that the City’s action was a Catholic conspiracy to punish him for having been a communist and pointed out in his 112± page affidavit of service that Mr. Kelleher, the mayor, Mr. LeForestier, the corporation counsel, Mr. Ryan, the building inspector, Mr. Bizzarro, a deputy corporation counsel, and the Pope were all Catholics. The "affidavit of service" of his notice of appeal was much more extensive than his actual appellate brief, which restated many of the same “facts” and arguments. Most interesting to me were exhibits included in the affidavit of service, such as an actual early 1900s letter that he wrote to his female friend while traveling to Germany to study zeppelins and a 1929 article that stated that he was the principal speaker at a physics convocation at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Although Kemp came to the law office to photocopy certain documents, he produced his legal papers with a typewriter, using a mimeograph to reproduce copies. His typing was not very good, and the documents were rampant with xxxx outs and careted corrections, making the reading quite difficult. (His typing improved somewhat over time as he produced hundreds of pages of pleadings.) Kemp was frugal, and to save money, he mimeographed his early pleadings on used paper. One document I saw, an Appellate Division brief, was printed “Central Markets” in green ink on the reverse side.

Although his legal brief did not address the issue on which Judge Taylor based the stay, the Appellate Division reviewed the record on appeal. It reversed the lower court order, remanding it to the lower court for a fact-finding hearing, which had never been held (it had acted solely on affidavits). Corporation Counsel LeForestier was so upset that Kemp had beaten him that he simply abandoned the case. Kemp, however, understood the decision to be the appellate court’s acceptance that he was the victim of a Catholic conspiracy. Kemp then launched a series of pro se lawsuits against the City of Troy and LeForestier, both in the New York Supreme Court (the lower general jurisdiction court) and in the US District Court, all of which were dismissed. I believe that he died soon after the last dismissal.

Wednesday, July 01, 2020

Tommy Conducts a Preliminary Hearing

|

| Justice Tommy Restino, Jr. |

The Town of Hoosick is a rural town in the northeast corner of Rensselaer County, at its border with Vermont. Its economy is mostly agricultural; mainly family farms. Its one village, Hoosick Falls, is an old mill town. Hoosick is a scenic area with some antique shops and is notable as the home of the late artist Grandma Moses. The Moses family still operates a farm with a roadside stand that sells excellent melons, corn, tomatoes, and other produce grown there.

For many years, one of the town justices has been Thomas Restino, Jr. He is an affable fellow who was usually reelected without opposition and endorsed by all political parties. In the late1960s, and for some time in that era, his main occupation was operating an Olixir brand gasoline station just south of Hoosick Falls on Route 22. Many criminal defendants and traffic violators arrested in the area were initially brought before Judge Restino, who was usually available during the daytime at his Olixir station. The court was frequently held right at the Olixir station, sometimes interrupted when Tommy would temporarily halt the proceedings to pump gasoline for a customer.

In the late 1960s, or perhaps in 1970, a rash of barn fires occurred in the Town of Hoosick. Ultimately, the New York State Police arrested several high school-aged young men from the community and charged them with arson. They were arraigned by Judge Restino on multiple felony charges. The law required that each young man have separate counsel, and I was one of several attorneys employed by parents or assigned by the court to represent the boys. All of the defense counsel demanded a preliminary hearing.

A preliminary hearing is a fact-finding hearing. It is held after a person is charged with a felony but not yet indicted by a grand jury. The purpose is to determine whether there are, in fact, grounds to have the matter presented to the grand jury for indictment. Defense counsel usually wants a preliminary hearing because it gives them the opportunity to cross-examine the prosecutor’s witnesses and find out the strength of the evidence against their client.

Judge Restino scheduled the preliminary hearing for an early weekday evening. Because there was so much public interest in the case, both by the victims of the arson and other farmers, as well as the families of the boys, the preliminary hearing was held in the high school gymnasium to accommodate the crowd. In addition to Gus Cholakis, the Rensselaer County District Attorney, some of his staff members, and New York State Police investigators, all of the defense attorneys attended. It was an unusually large and somewhat boisterous crowd that Tommy had to preside over. A record of formal court proceedings is required. Usually, a court employs a professional court reporter who (in that era) typed a verbatim record of everything said into a stenotype machine, and later translated the paper record into a typewritten transcript. There were no professional court reporters in the Town of Hoosick, and rather than bring one in from Troy, Tommy employed two young local women who knew secretarial shorthand. He instructed one of them to record the attorneys’ questions and the other to record the witnesses’ answers. Although the ladies tried their best, the system's inadequacies were apparent when an attorney asked for some testimony to be read back. Listening to them try to coordinate the questions and answers was quite amusing, and I think that sometimes attorneys requested that testimony be read back simply for their amusement.

Each defense attorney had a separate right to cross-examine each prosecution witness and the proceedings dragged on. Tommy struggled with objections to testimony made by the several defense attorneys, as he was a layman with no legal training. At one point when he sustained a defense objection to some evidence, the victims in the room started loudly voicing their displeasure at his ruling. Tommy explained to them that he personally didn’t always agree with the rulings that were made by him as the judge, and he spoke of himself as the judge in the third person: "I don't agree with him, myself, but he is the judge and that's how he had to rule."

The preliminary hearing could not be completed in just one evening and dragged into a second night. After each session was adjourned, the prosecutor, his staff, some of the police investigators, and some of the defense counsel stopped at Brother John’s seedy tavern on Route 7 in Pittstown for a few drinks and a discussion of the proceedings, which were an amusing change from usual court appearances.

Ultimately, Judge Restino determined that the district attorney had produced sufficient evidence, and the Rensselaer County Grand Jury subsequently indicted the boys. Because of their ages and previously unblemished histories, plea bargains were reached and the boys pleaded guilty to lesser charges. They were placed on probation by the County Court.

Tuesday, June 02, 2020

Harry and the Trooper

Sometime in the early 1950s, my uncle, Harry Honig, bought a gas station about a quarter-mile east of Jack’s Place. It had been a garage and gas station operated on and off since the 1930s. As a child during World War II, I remember that it had a small red siren attached to it that was powered by the garage’s air compressor, and I can still recall how the siren’s shrill sound announced that it was time for my father to don his white hat and stop traffic during the air raid drills.

Harry bought the garage to give him something to do during winter when he was not farming. For a year or two, during the summer months, his daughter, Leona, operated the gas station since Harry would be busy on his farm. The structure was a wooden structure with a tin roof. Harry was not a mechanic and didn’t do any automobile repairs there; he operated the facility as a gas station and a place to store his farming equipment off-season. There were two gas pumps: one for regular gasoline and one for “Ethyl,” or high-test gasoline. Like the driveway at Jack’s Place, Harry’s driveway consisted of small multicolored pebbles bought by the dump truck load from some supplier in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The pebbles were about one to two inches deep and had to be refreshed every couple of years as the weight of automobiles would eventually press them into the dirt base.

One Sunday morning, Harry arrived at his gas station and found that a large “18-wheeler” tractor-trailer had parked in his driveway, perpendicular to the highway, obscuring the view of the gasoline pumps for westbound drivers on Route 20. The truck driver was nowhere in sight, and there was no message on the vehicle explaining why it was parked there or where the driver was. Harry was angered and frustrated as he felt that he was losing business. Finally, he parked a tractor that he had stored in the garage closely in front of the truck so that it couldn’t be moved. Later that day the driver returned, and Harry demanded some small monetary compensation before he would move the tractor and free the truck. The truck driver refused and left. The truck drive contacted the New York State Police, who dispatched a young Trooper to the garage to resolve the problem.

The Trooper ordered Harry to move the tractor, but Harry refused, telling the Trooper he would move his tractor when he was paid. They argued, and the Trooper realized he was powerless to make Harry comply with his directive since the truck and the tractor were on Harry’s private property, where he had no jurisdiction. Angered, the Trooper got into his gray Ford patrol car and ripped out of the driveway, spinning the wheels of his vehicle as he traversed the driveway, sending the pebbles flying and leaving two parallel ruts in the driveway down to the dirt base.

The Trooper didn’t know Harry and certainly didn’t know that Harry had been the Nassau town’s Justice of the Peace for many years and was currently its elected Town Supervisor. Harry, of course, knew all of the senior members of the State Police stationed at the barracks in East Greenbush, and he telephoned the barracks and explained the situation to the Sargent in charge, detailing how this brash young Trooper had torn up his driveway.

About an hour later, the young Trooper returned with a very different attitude. After some discussion, the truck driver gave Harry an agreed-upon sum of money as compensation for his lost business, and Harry moved the tractor and the truck left. Then Harry gave the Trooper a rake and, with satisfaction, supervised him as he raked the pebbles to fill in the ruts he had created, as he had been ordered to do so by his Sargent.

Friday, May 01, 2020

Harry Prepares for Nuclear War

My uncle Harry Honig was a Nassau Justice of the Peace and then Town Supervisor during the onset of the Cold War. He was genuinely civic-minded, although he undoubtedly enjoyed the social aspects and perks of his offices. As part of the Civil Defense effort during the Truman years, he spent many hours as a volunteer of the Ground Observer Corps sitting in the stands of the old Nassau Fairgrounds racetrack watching for Russian airplanes, dutifully calling in any aircraft he sighted to the Civil Defense filter center in Albany. [That program had one very embarrassing local incident: A teenage aircraft volunteer spotter at the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building in Albany reported a multi-engine aircraft flying north over the Hudson River. There was no flight plan for such an aircraft, and the Civil Defense alerted the Air Force. Two fighter jet aircraft were scrambled from Westover Air Force Base near Worcester, Massachusetts to intercept it, and they almost fired upon President Truman’s personal aircraft, The Independence, which was ferrying Secretary of State Dean Atchison to Canada.]

My uncle Harry Honig was a Nassau Justice of the Peace and then Town Supervisor during the onset of the Cold War. He was genuinely civic-minded, although he undoubtedly enjoyed the social aspects and perks of his offices. As part of the Civil Defense effort during the Truman years, he spent many hours as a volunteer of the Ground Observer Corps sitting in the stands of the old Nassau Fairgrounds racetrack watching for Russian airplanes, dutifully calling in any aircraft he sighted to the Civil Defense filter center in Albany. [That program had one very embarrassing local incident: A teenage aircraft volunteer spotter at the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building in Albany reported a multi-engine aircraft flying north over the Hudson River. There was no flight plan for such an aircraft, and the Civil Defense alerted the Air Force. Two fighter jet aircraft were scrambled from Westover Air Force Base near Worcester, Massachusetts to intercept it, and they almost fired upon President Truman’s personal aircraft, The Independence, which was ferrying Secretary of State Dean Atchison to Canada.]As Town Supervisor, Harry received a stream of civil defense information and he became well versed in the dangers of the nuclear age. Harry studied civil defense maps of fallout patterns and concluded that Nassau would receive radioactive fallout carried by the prevailing westerly winds even if the bomb fell as far away as Chicago. In fact, most of the east coast of the United States was vulnerable.

One area that appeared safe from nuclear war was the Isle of Pines, part of Cuba. Like much of the Caribbean area, it was south of the United States, and the winds would not deposit radioactive fallout on it even if the United States were to be attacked. Harry was a farmer, and he read that the Isle of Pines had rich farmland that he could acquire very inexpensively by American standards. After the farming season was over in the fall of 1958, Harry and Frieda headed to Cuba to search out farmland so that they could create a home that was safe from nuclear war. Unfortunately, they arrived there at about the same time as did Fidel Castro’s rebel army, and they spent a couple of days holed up in their hotel as the Cuban revolution went through. Harry immediately grasped that although they might be safe from radioactive fallout in Cuba, they would face perhaps greater danger from the revolution. Harry and Frieda next scouted out Arizona but found the hot climate disagreeable and the land unsuitable for his type of farming. Reluctantly, they returned to Nassau.

Harry was not one to give up easily. He promptly had a large underground concrete fallout shelter constructed behind his home using a plan obtained from a civil defense organization. The shelter had a hand-powered air pump that brought in outside air through a filter, and he stocked the shelter with canned water, food, fallout shelter crackers, and a battery-operated radio.

After a while, the nuclear threat diminished, and the shelter became dank and probably the home to creatures that like living in such an environment. In his later years, it was forgotten, fortunately without ever having been used.

Wednesday, April 01, 2020

Nassau Murders

Sunday, March 01, 2020

Halloween

Halloween was a major holiday in Nassau. Local youths loved to go to Fauth’s cider mill on Lake Avenue to swipe apples from the open bins. “Trick or Treat” in those days meant something. Little kids didn’t go door to door with their mother. Halloween was the night that the older boys went house to house, raising a little hell, soaping car windows when the owners didn’t keep a watchful eye. The mean boys used candles instead of soap. Candle wax was much harder to clean off. Years before, Halloween was a night to tip over out-houses, but those had all pretty much gone from the Village by the time I was a child.

A big part of Constable Harrington’s job was to keep the level of mischief down. He would drive slowly through the Village on Halloween night, shining the chrome spotlight along the houses to check for mischief-makers. He would yell at the groups of boys to move along, an action that was frequently met with a barrage of the pilfered Fauth apples before the boys scattered into the shadows, only to reappear a few minutes later after he passed by.

Early one Halloween night, I think the last one when Will was Village Constable, he stopped by Frank Pitts’s General Store. Frank’s store was next to the Post Office at the corner of Church Street and Elm Street, where the antique store is now. Will went in to get a pack of cigarettes and shoot the breeze for a few minutes with Frank. He parked the Hudson in the pull-off by the closed Post Office but left the car’s engine running. When he came out a few minutes later, his Hudson was gone.

It was the grandest Halloween ever! Will was both enraged and embarrassed, as he walked around the Village looking for his car, and threatening every one of the older teenage boys and young men that he spotted. Word of the theft got out quickly, and it was an open season that night for apple stealing, apple throwing, and soaping and waxing windows. Some of the boys took advantage of the situation and even busted up Halloween pumpkins put out as decorations on some porches.

Halloween night eventually faded into November first, but there was no sign of Will’s Hudson the next morning. Poor Will had to hitch a ride to his regular day job that morning, and by the time he came home that evening everybody in the Village knew of Will’s plight and was ready to offer a theory as to who had done it, and where his car was. They say that Constable Harrington walked all around the Village that night, looking for his Hudson in barns, behind hedgerows, and wherever he thought it could be hidden, but there wasn’t a trace of it.

The next night, a little after seven, Frank Pitts called Will to tell him that the Hudson was parked in front of the Post Office with the engine running.

Saturday, February 01, 2020

Wyatt shoots a dog

Wyatt upheld the law. Nassau’s perceived problem was speeding. U.S. Highway 20 formed the main street in the Village, Albany Avenue west of the single traffic light, and Church Street to the east. Cars and trucks entering the Village from the east descended Lord’s Hill for about a mile and a half and usually entered the Village at a pretty good clip. The speed limit went from 50 miles per hour to 35 miles per hour to 25 miles per hour in a short distance, but it was not unusual to still be driving about 40 miles per hour when crossing into the 25 mph zone.

Wyatt would be waiting. He usually parked his new cruiser in the St. Mary’s Church parking lot and ticketed every speeder he believed exceeded the posted limit. There were many of them. The Village judge, James Lamb, was a retired New York City fireman with a lot of time on his hands, and he welcomed the Court activity that all of the tickets produced. The Village Trustees welcomed the added revenue it gained from its share of the fines. At the time, the Village judge held court one evening each week, but the court would always be in session at his home, and Wyatt would lead out-of-town speeders right to Judge Lamb’s living room, where they would be promptly fined and sent on their way. Nassau soon earned a measure of notoriety as a speed trap and was appropriately marked on AAA maps. Almost everyone who drove through Nassau had been ticketed by Wyatt or had a friend or family member who had been caught. The locals quickly learned to obey the speed limit because they knew that Wyatt played no favorites, and he had no compunction about writing a speeding ticket for “26 mph in a 25 mph zone.”

I never got a ticket, but I was careful. I used to drive my father’s new 1956 pink and black Cadillac into the Village to pick up the mail, and I would put on the brakes to ensure I was doing 25 mph or less. I sometimes played a little game with Wyatt. If he pulled out to follow me down Church Street, I would pace myself to have to stop at the traffic light. When the light turned green, I would floor the Cadillac so that it would chirp the tires, but then immediately back off on the accelerator so that I wouldn’t exceed the speed limit. Then I would go to the Post Office. Wyatt would usually follow me out of the Village at 24 mph unless he was in the process of writing a ticket for someone else.

By the time Wyatt was the chief for a couple of years, his notoriety grew. He seemed to walk taller, always wore mirrored Ray-Ban sunglasses, and carried a long-barreled .44 Magnum sidearm. He was an imposing figure, and Nassau knew it had a real lawman.

One Saturday afternoon, a pickup truck drove down Church Street. It had the green light and was moving right along. A dog ran out, unleashed, right into the path of the truck, and the animal was struck, severely hurt, but not killed. Wyatt was quickly on the scene, and a crowd of residents assembled, most of them coming out of the Post Office or Frank Pitts’s General Store, when they heard the screech of brakes. The dog was whimpering, and after a brief examination, the consensus was reached that the dog should be put out of its misery. The dog’s owner, not wanting to make the dog suffer any longer than necessary, looked to Wyatt to do the job. With the crowd growing larger and traffic backed up, Wyatt drew his .44 and fired. The bullet missed the dog and tore a chunk of macadam out of the payment. Wyatt shot again and again he missed the dog. He seemed to be grimacing and looking away as he fired his revolver. A bystander, one of the local merchants, took the gun out of Wyatt’s hands and dispatched the dog with one shot, much to the relief of everyone witnessing the event.

After that, things changed in Nassau. Young men who hung around the Gulf gasoline station on the corner started calling Chief Avery “Wyatt” to his face. Teenage boys barked at him and laughed. Wyatt seemed to lose interest in writing tickets, and the court revenue dropped off sharply. Then, one day, Chief Avery moved on to take a job directing traffic as a foot patrolman in Lake George, and it was ok to drive a bit faster through Nassau.

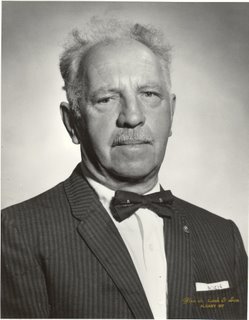

|

| Chief Avery |

Wednesday, January 01, 2020

Chasing Speeders

The Village fathers wanted their policeman to slow speeders, help the elementary school children cross Route 20, and be available to handle the occasional domestic dispute. Instead, they usually hired someone who wanted to tackle criminal investigations that would stump Interpol. That was not the case with Marty. He was low-key. He wrote a few tickets, helped the kids cross the street, directed Sunday morning traffic when the churches let out, and generally did whatever the Village Trustees thought he should do. He was a pretty good fit for the Village. While nobody had a bad word for him, he didn’t command much respect, probably because of his somewhat disheveled appearance. Once, Marty came to a meeting of the Village Trustees to complain that an out-of-town driver he had ticketed had ripped it up and mailed it to him, addressed only to “Marty, the Fat Fuzz, Nassau, New York.” He seemed most upset that the Post Office had delivered it to him matter-of-factly. The Village Trustees nodded their sympathy, but none shared his indignation.

Marty became friendly with Wilbur, a recent retiree from New York City who had worked as a lineman for Consolidated Edison. Wilbur had been a volunteer auxiliary policeman in New York, meaning he rode around in a police car at night with a patrolman but had no police officer status. The auxiliary policeman served a useful purpose, keeping the police officer company, providing “an extra pair of eyes,” and being ready to radio for help in an emergency. Although the village had no formal auxiliary police program, Wilbur started riding with Marty to pass the time. The Village Trustees were aware of this but saw no harm, particularly since there was no expense. Wilbur even created a makeshift uniform, but he looked more like an aging security guard than a policeman.

During the 1960s, the Capital District cities of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady experienced some racial strife. A group of young Black men in Albany, leaders of that city’s protest movement, smashed some store windows during a demonstration one night, and several of them were arrested, but there was no real personal violence. That event was replicated in Troy and Schenectady and was a major news source for a while. During the height of this tension, Marty and Wilbur came to the Village Trustees, and Marty told them that he had to prepare the Nassau Police Department for this new law enforcement crisis. He had a wish list of new gear, including a pump shotgun, 2 riot helmets, 2 bulletproof vests, and some tear gas canisters. As their counsel, I unsuccessfully argued against Marty’s request, pointing out that I had only known of two young Black men in the Village. One, “Sunshine” Fairbanks, had gone to elementary school with me but had long since moved away, and Harold Hallenback, a young man two grades behind me, whose family had lived just outside of the Village for a couple of generations. While the Trustees nodded in agreement that Harold was unlikely to pose a threat, they felt that they owed an obligation to Marty to equip him with the equipment he said he needed for his safety. They also apparently felt the same obligation to Wilbur since they authorized two helmets and two vests. Marty and Wilbur rode around wearing their helmets and vests for a few weeks, with a pump Mossberg 12 gauge handy on a special rack. After a while, though, the newspaper headlines returned to normal, and the helmets and vests went into the patrol car's trunk. But if Harold ever walked into the Village and got rowdy, Marty and Wilbur would be ready.

Marty attended the Village Trustees' one September board meeting at Wilbur's prompting. He reported that the Village had become a “laughingstock” because he wasn’t permitted to chase speeders outside the Village corporate limits. Speeders would taunt him by racing through the Village, knowing he would not follow. While the law permits a police officer in “close pursuit” to travel beyond the territorial limits of his community to make an arrest, many communities had a policy restricting their officers from doing so because so many high-speed chases resulted in tragedy, frequently to innocent bystanders. Marty asked for permission to chase speeders outside of the Village. The Trustees were not enthusiastic, but neither did they like being the elected officials of a community that was becoming known for its lack of traffic law enforcement, especially considering its reputation as a speed trap just a decade before. The trustees finally agreed that Marty could, in appropriate cases, chase traffic violators outside of the Village.

When I drove into the Village for the October board meeting, I was surprised to see a shiny new police car parked in front of the Village Hall. I knew there was no appropriation for purchasing a new police car during the fiscal year, and I asked Mayor Strevell how they got it. Remembering that I had cautioned the Village Trustees against permitting close pursuit chases at the previous meeting, he was a little sheepish in explaining to me that the very Saturday after the previous meeting, Marty and Wilbur went in pursuit of a speeder heading west through the Village on Route 20. With the siren screaming and the red lights flashing, Mary drove the cruiser out of the Village and into the Town of Schodack. The speeder went faster and faster, and so did Marty and Wilbur. They raced past the veterinary clinic on the left and the fruit stands on the right, up Bunker Hill, and past Thoma Tires. As they neared Schoolhouse Road, Marty got closer and closer to the speeder, less than 100 feet from his rear bumper. Marty didn’t immediately realize that the reason he was closing the gap between the cars was that the speeder was slowing down to make a right turn into Schoolhouse Road. Instinctively, Marty turned right also. That had been a mistake because Marty lost control of the cruiser when the tires slid on the gravel of Schoolhouse Road, and the police car slid into a stand of lilac bushes and rolled over onto its side. Fortunately, Marty and Wilbur were shaken up but were otherwise unhurt except for a bruised ego.

Getting back to the new police cruiser, Mayor Strevell explained that the wrecked car would have taken at least a month to have fixed, and the Village couldn’t be without a police car for that long a time, especially with Halloween coming. Marty and the Mayor called the Dodge dealer in Albany, who promptly arranged a trade-in with the Village’s insurance company and delivered a new replacement for the wrecked car. Although nothing was said at the Village Board meeting, Marty didn’t chase speeders out of the Village again, and Wilbur’s wife decided that Wilbur should spend his spare time helping out around the house instead of riding with Marty.

Marty continued as Nassau’s police officer for several uneventful years until he had enough time in the New York State Municipal Retirement System to be eligible for a pension. He spent his remaining years as a security guard in a home for the aging in Albany.