There were few job opportunities for our Albany Law School graduating class of 1963. A few classmates were the sons of practicing attorneys, and most of them joined their fathers’ firms. A few got positions in prominent law firms, but many had to defer job hunting until completing required military service that had been deferred through college and law school. Some had no job prospects at all. I was part of that group.

After taking the bar exam in July, I started making the rounds of Troy law firms. I wanted to practice in Troy because the previous summer, I had a non-paying internship at the Rensselaer County District Attorney’s Office. I was familiar with the courthouse and the Supreme Court law library and had met several attorneys and court personnel. I started knocking on doors and finally got two offers. One offer was from Seymour Fox, who had a storefront office on River Street, and the other was from Steve Vinceguerra, who had a solo practice on the second floor of a brownstone multifamily building he owned on third or fourth street. Both offered a salary of $50.00 for a five-and-one-half day work week. I asked John T. Casey, the District Attorney for whom I had worked, and taken an elective criminal law course, which of the two offers he would recommend. He said it was a toss-up. I decided to go with Seymour Fox because I disliked the cooking smells that filled the air in Mr. Vinceguerra’s office and building.

I was given a small office and was promptly put to work drafting automobile accident and sidewalk fall-down complaints. Law school did not teach us the art of drafting pleadings, although we were aware of form books. Seymour had a very active tort practice, and many of the pleadings were simply pro forma documents prepared by clerk typists, copying from pleadings used in other cases. Fortunately, another attorney, Frank DeCotis, was employed in the office. He was a contemporary of Mr. Fox and perhaps a bit older than him. Frank had once been Seymour’s partner but left the practice for a time. He eventually returned as an employee. I frequently asked Frank for help, which spared me the humiliation of asking the clerk typists or secretary questions of a legal nature. Eventually, I was promoted to drafting bills of particular, affidavits in response to motions to dismiss, or to timely respond to demands for bills of particulars. I had poor handwriting but was an excellent typist, and Seymour provided me with an electric typewriter, which I used to churn out letters and documents.

For many years the procedural law had been governed by the Civil Practice Act. While I was in law school, the New York legislature enacted its successor, the Civil Practice Law and Rules (“CPLR”), which by its terms took effect on September 1, 1963. Accordingly, while we studied the Civil Practice Act during our freshman and junior years, we studied the CPLR during our senior year, and I was more knowledgeable about its provisions than most practicing attorneys. I was eager to impress Seymour with my knowledge. Shortly after September 1, I was given an answer and demand for a bill of particulars in an automobile accident case. The defense counsel was an Albany law firm that specialized in tort defense for insurance companies. At the time, most litigation documents were written on 8-1/2" x 14" legal-size paper. I knew that the CPLR specified that legal pleadings were to be 8-1/2" x 11" letter-size paper. I returned the pleading to Carter & Conboy, the defense counsel, with a letter pointing out that the pleading did not comply with the provisions of CPLR Rule 2101 (a). I thought myself very clever, but a couple of days later, I received a dressing down from Seymour, who had received a telephone call from an irate defense counsel. Seymour explained that attorneys simply did not hold other attorneys to such technical perfection. (The pleadings were resubmitted; however, they were on paper of the proper size.)

Seymour’s office was unique for a law firm of its size in that it had a Xerox 914 plain paper photocopier. Because of this, typists only had to produce a good original document. Most law firms of that size didn’t have a photocopier, and typists usually had to make several carbon copies of documents. Spirit mimeograph copies were made for standard documents, such as a demand for a bill of particulars, which only required the typist to enter the parties’ names and a date. The Xerox was unreliable and usually required at least one service call each week. The machine was rented, and the charge was based on the number of copies made. Seymour kept a SCM photocopier as a backup, but using it was laborious, as the copies came out wet and dried curled. (In the early 1970s, I rented a Royal plain paper photocopier that made excellent copies, but after a few months, the ink would literally fall off the paper.) Seymour liked technology and gadgets. He was one of the first local offices to buy an IBM Electric typewriter that recorded the keystrokes on magnetic tape to easily edit documents - one of the first true word processors. Seymour also had an elaborate telephone call recording device that recorded all telephone conversations from his private telephone. The device was legal in New York, and Seymour wanted to be able to recall every detail of his conversations accurately.

Seymour was not well-liked by many attorneys whose practice was primarily tort law. Some considered him to be an upstart, and they thought he must have been an ambulance chaser to have developed such a large and lucrative practice so early in his career. I discovered the depth of that feeling on the day of my admission to the bar on November 14, 1963. Candidates for admission merely submitted a short form to the Third Department’s Character and Fitness Committee, with the signatures of three attorneys who vouched for the candidate’s good character and fitness to practice law. Mine was signed by then-District Attorney John T. Casey, another attorney whose name now escapes me, and by Seymour Fox. As we prepared to go into the Appellate Division Court Room on the 3rd floor of the Albany County Court House, each candidate would meet briefly with the Committee, which welcomed them to the profession. To my horror, when it was my turn, I was told that I was not to be admitted because one of the local members of the Committee, an insurance defense counsel, said that Seymour Fox was not of good character and he would not recognize him as a proper attorney to recommend my admission to the Bar. Finally, after some consultation with John O’Brien, the Clerk of the Appellate Division, the Chairman told me that I would be admitted but that I should supply a new application signed by another attorney and suggested Morris Zweig, my father’s attorney and a justice of the peace in my home town. When I told Seymour what had happened, he explained that some of the attorneys thought he was getting clients by unethical means and threatened a bar association investigation of his practice. As a defensive measure, Seymour employed several private investigators to interview accident victims represented by the attorneys who questioned Seymour’s ethics to determine why they chose their respective attorneys. He said that when it became known that he was having his critics professionally investigated, his critics quieted. During the nearly six years I practiced with Seymour, I never saw any evidence of unethical conduct. His practice thrived because he was tenacious and generally got quick settlements for his clients. Troy was a close-knit community, and word of mouth was his source of clients. He was also frequently recommended by some physicians since he always ensured his client’s medical bills were paid out of settlement funds. Seymour was glib and an excellent trial lawyer, frequently being asked by other attorneys to try their cases. I never submitted an additional reference to the Committee.

Law practice in the Capital District was much different in the 1960s than it is now. There were fewer lawyers, and the practice was relatively informal by today’s standards. Any attorney could issue a bare summons to commence an action without any court filing or payment of a fee. In most cases, stipulations to extend the time to serve a pleading or a bill of particulars or to adjourn a proceeding were made by a telephoned agreement without a written follow-up. Seymour mentioned the names of about eight attorneys in the Capital District who he felt could not be trusted to uphold an oral agreement but said that all others would honor their word.

All motions were heard at a “special term” of court. In most courts of the Third Department, the special terms were held on Fridays, once or twice a month. In Albany, however, they were held every week because of the caseload, as most proceedings involving the State of New York had to be brought in Albany County. While a special term note of issue had to be filed with the court clerk to place the motion on the calendar, no fee was required. Special terms consisted of Part I, which were regular litigation motions and proceedings, and Part II, for uncontested matrimonial actions. (Before the enactment of “no-fault divorce” laws, all matrimonial cases, including uncontested and default matrimonial actions, had to be heard by a Supreme Court justice). Special Terms were exciting and educational for new attorneys. The mimeographed calendars were distributed on the morning of the Special Term. There were frequently more than one hundred motions and special proceedings listed. The clerk would call out the cases in order, and the attorneys would yell out the responses for their cases, such as: “adjourned by consent”, “off”, “settled”, “20-day order by consent” or “order if no opposition”. Motions or proceedings that were to be argued were noted by a call of “ready for the plaintiff” or “ready for the defendant.” If there was a routine consent order or a default order, it would be handed up to the judge who would usually sign it and hand it back. After the calendar call, the Part II judge would hear matrimonial cases in chambers, usually in a conference room. The Part I justice would listen to oral arguments of the contested motions or proceedings in the main courtroom. It was the practice in the Third Department that the motion papers would be handed up to the Part I justice at the start of the oral argument, and the judge hearing the argument had no prior knowledge of what it was about until the start of the argument. In contrast, the practice in the neighboring Fourth District required that motion papers be submitted to the Part I judge several days before the special term. As a result, the Part I judges there were in a much better position to understand the issues before them. The real benefit to the new lawyer was that the special terms allowed him the opportunity to become familiar with other attorneys, judges, and court personnel and to learn the court's rituals. I quickly learned that Justice Edward Conway was both knowledgeable and gracious to all attorneys, while Justice Isadore Bookstein was someone to be avoided except for consent orders.

Shortly after I was admitted to practice, Seymour introduced me to an alternate procedure for handling uncontested divorces. Some clients from Rensselaer or Albany County didn’t want their divorce to be public knowledge. For those who could afford the additional expense, a quick trip to Mexico was the solution. The client would be met at the airport by the Mexican attorney, taken to a hotel, and the next day would appear before a Mexican judge who would grant the divorce. The Mexican attorney would then forward the judgment of divorce written in Spanish with an English translation.

For some clients whose divorce was uncontested and who could not afford or want a Mexican divorce, the solution frequently was a trip to Schenectady. Although a hearing for divorce is usually brought in the judicial district where the case is pending, it could be brought in a county in an adjacent judicial district. One day, Seymour brought me to an uncontested divorce hearing in the Schenectady County Court House. The hearing was held in the chambers of Supreme Court Justice Charles M. Hughes. Instead of a court stenographer recording the testimony with a stenotype machine, Marie, the judge’s private secretary kept the minutes in shorthand. Seymour left a proposed Decision and a proposed Judgment of Divorce with Marie, and a few days later, Marie mailed back the pleadings and the signed Decision and Judgment, together with her stenographer’s bill for twenty-five dollars. Shortly after that, Seymour arranged for me to bring a divorce client to Judge Hughes, and I followed the same procedure. Justice Hughes listened to the testimony and stated that the divorce was granted. The next time I called Marie and set up a divorce hearing, I was in for a surprise. Justice Hughes wasn’t there, but Marie said we should start the testimony anyway. This development caught me off guard, and when I neglected to ask some pro forma questions, Marie would ask them of the client. The transcript that I received indicated that Justice Hughes had asked those questions. This procedure was thereafter routine. Divorce hearings were scheduled in the afternoon at a mutually convenient time. Sometimes, Justice Hughes would be in attendance, but more frequently, he was not.

I handled most of the Troy Police Court cases for Seymour. He didn’t relish routine criminal cases but took them when asked to keep his contacts within the community and his name in the newspaper. The defendants were frequently clients or relatives of clients. Most criminal cases were minor misdemeanors and were resolved by a plea bargain. Neither the part-time police judge nor the part-time assistant district attorneys were usually interested in a trial, and a defense demand for a jury trial usually helped bring about a satisfactory resolution. Frequently, there was a military disposition in the case of young men without a prior criminal record. Military recruiters frequently showed up in Police Court and were eager to review the record of such defendants and advise the court and the attorneys whether the defendant was eligible for enlistment, except for the pending criminal charge. Faced with possible jail time and the disgrace to him and his family, many young men agreed to enlist. Upon their acceptance, the criminal charges were dismissed. In fact, I once arranged a military disposition for a cousin who was a student at Hudson Valley Community College. He had done something foolish and been arrested. Although I suggested that he join the Army, he insisted on becoming a Marine, which, as it turned out, was not a good choice for him. He couldn’t take the rigors of boot camp and soon was discharged.

Fees and costs were very low by today’s standards. Except for tort claims in which the plaintiff’s fees were usually equal to one-third of the settlement or judgment, plus expenses, attorneys’ fees were calculated quite differently. Each county bar association published a list of minimum fees that its members could charge, and it was an ethics violation to charge less than the scheduled amount. That eventually changed when the United States Justice Department determined that minimum fee schedules constituted an illegal restraint of trade. When the minimum fee schedules were in effect, most attorneys charged by the type of transaction rather than by an hourly rate. Many lawyers prepared wills without charge, hoping to represent the estate when the client died, and it was not uncommon for the attorney to insert a provision in the will specifying that the attorney was to be retained to handle the client’s estate.

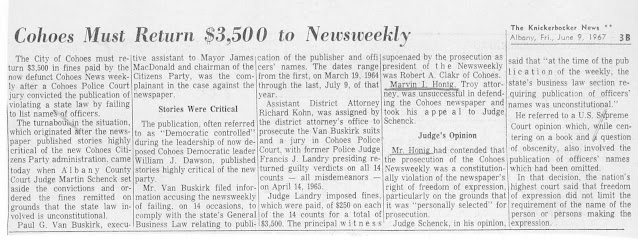

Once I was admitted to practice, Seymour raised my salary to $55.00 per week, but I was required to give him 1/3 of any private practice fees I developed independently. Later, as an incentive to stay, He named the practice “Fox, DeCotis & Honig,” and Frank and I were to split 1/3 of his negligence fees as a bonus. That worked for a short while, but eventually, Seymour felt that our bonuses were too large and did away with that arrangement instead by giving us both substantial salary increases. Knowing I would never be a real partner in the firm, I left in March 1969 and opened my own practice. I rented office space from Lawrence Connors at 41 Second Street on the corner of Second Street and Broadway and had the use of his secretary and library. Larry was an interesting and affable fellow. He was the nephew of Marty Stack, the Rensselaer County Clerk, and a power in the Rensselaer County Republican Committee. Through that connection, Larry had been appointed the Troy Corporation Counsel. His legal acumen was somewhat limited, but he bragged that he knew which other lawyers he could call to find out the answers to legal questions and not have to do much research himself. His political/legal career had come crashing down when it became known that he was the "13th man" arrested (but released without being charged) in a gambling raid conducted by Troy police officer George Dodge, who arrested a group that had a regular friendly card game. It was said that Officer Dodge undertook to arrest some locally prominent individuals in retaliation for having his shift changed. I later represented Larry in a hearing before the New York State Commission of Investigation, which conducted hearings in New York City and Troy into alleged corruption practices. Larry was never charged with any wrongdoing and unfortunately died relatively young a few years later.

When I opened my own practice, I only had about half a dozen files of my own, but I had acquired some professional credibility and public awareness as a result of the reapportionment action that I had brought against the County and was frequently mentioned in the newspaper when I appeared as a criminal defense attorney for Mr. Fox's clients. Shortly after opening my practice, I was assigned to represent Edward F. LaBelle in the retrial of his murder indictment. He had previously been convicted, along with his brother, Richard, of the 1963 rape and slaying of a teenage girl from Cohoes, whose body had been found in a culvert in Schaghticoke. Originally, both he and Richard were found guilty and given death sentences, but the Court of Appeals reversed the convictions and ordered separate trials. Thomas J. O'Connor, a former Troy Police Court judge and Public Defender, represented Richard in both trials. No Troy criminal attorney wanted the assignment because they all knew it would be a lengthy trial for little compensation and the notoriety of being associated with a defendant charged with a heinous crime. Edward was again convicted. He received a life sentence and eventually died in prison, never having asked to be paroled. (Richard was eventually paroled).

I met James J. Reilly when I interned in the Rensselaer County District Attorney's Office during the summer of 1962. He was a part-time Assistant District Attorney then, and I started handling some matrimonial cases for him after I opened my own practice. Jim had been sharing space with a relative through marriage, Matthew Dunne, but he had the opportunity to rent an attractive turn-of-the-century building at 54 Second Street with the option to buy it. He invited me to join him, and we used the firm name 'Reilly & Honig,' but our practices were separate. It was an expense-sharing relationship, and we eventually bought the building and stayed together until the mid-1980s, when I moved my practice to Albany. "Country Jim" (distinguished from "City Jim" - another attorney with the same name) was very low-key but had a fine legal mind and a droll sense of humor. We usually had lunch together every day, absent conflicting schedules.